By Colin McNaughton, Farms.com Risk Management Intern

The 2023/24 South American weather scare could be a game changer for corn in Brazil and globally.

Large-scale deforestation of the Amazon rain forest began in the 1960s, but it accelerated under former Brazilian President Jair Messias Bolsonaro (in office 2019–2022), reaching a fifteen-year high in 2021.

Scientists have warned that the world’s largest rainforest is approaching a critical tipping point. If that point is surpassed, there could be severe, irreversible consequences for the planet.

The tipping point was estimated at 20 to 25 percent deforestation.

The deforestation—the rainforest is not only home to untold species of flora and fauna, many of which are uncatalogued—will also affect the forest’s ability to recover from droughts, fires, and landslides.

Continued deforestation could also cause dieback—a situation whereby the wet, tropical Amazon climate dries out.

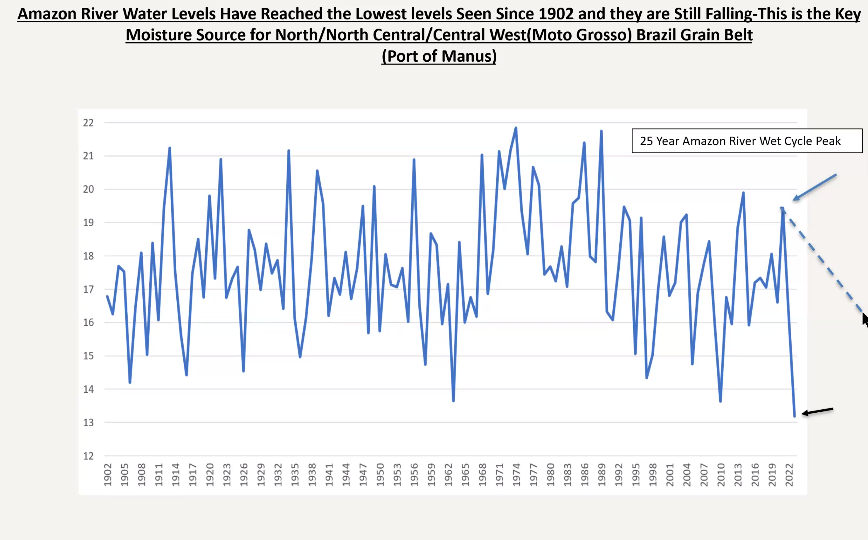

Now, at a calculated 20 percent deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil, the Amazon River—the second largest river in the world after the Nile at 6,400 kilometres long, give or take—is fighting severe drought conditions and is seeing low water levels not seen in 121 years.

It has given South America the worst start to its growing season ever.

The repercussions of this extended dry spell are rippling through the country’s agricultural sector, causing concern for grain exports and crop yields, mainly corn and soybeans.

This situation has profoundly impacted Brazil’s grain export activities, with significant economic repercussions.

Corn and soybeans, two of the country’s key exports, have been particularly affected. Shipments have been disrupted and forced to redirect to more southerly ports, such as Santos—Brazil’s primary grain terminal—albeit at a higher cost.

Brazil’s corn export prices continue to undercut those of major competitors, but the gap has been narrowing due to the logistical challenges posed by the drought.

The extended weather forecast for South America through November is grim, indicating a continuation of the stagnant weather patterns of hot/dry (heat is off the charts) and too wet down South. This poses a significant threat to the country’s soybean and corn crops, with potentially devastating consequences.

The delay in planting Brazil’s second Safrinha corn crop (75 percent of the total production) in the spring of 2024 is particularly concerning. Monsoon rains could end earlier than usual, at the end of March or early April, which could have long-lasting effects on the country’s agricultural output.

“Safrinha” is Portuguese for “little crop,” as the second crop was once smaller than the first crop.

The severity of the situation lies in the potential failure of the monsoon rains, which are critical for the region’s crops. Brazil is on the brink of a crop failure if these rains falter. Furthermore, the extreme heat remains a significant concern.

The current dry spell, extending back to 2020 and even as far as 1980, has resulted in an evaporation index so high that even if rain does fall, it feels like it never occurred. This challenges crop resilience, as traditional genetics may not withstand these extreme temperatures.

Due to the dire weather conditions, many crop experts have been compelled to revise their estimates downward.

One such expert, Dr. Michael Cordonnier of Soybean and Corn Advisor Inc. has lowered his estimate for Brazilian corn and soybean production by two million tons (mt) each, now at 123 MMT (million metric tons) for the corn and 160 MMT for the soybeans. He maintains a lower bias for both crops, which remain record-large.

Dr. Cordonnier pointed out that soybeans planted or replanted under these erratic weather conditions face a heightened risk of lower yields, particularly in east-central and northeastern Brazil.

This is the earliest that Dr. Cordonnier has lowered South American estimates, which could be the start of further production reductions in the future.

Some analysts, experts, and weather forecasters estimate there will be as much as a 15-20 percent production hiccup if the weather pattern does not change soon.